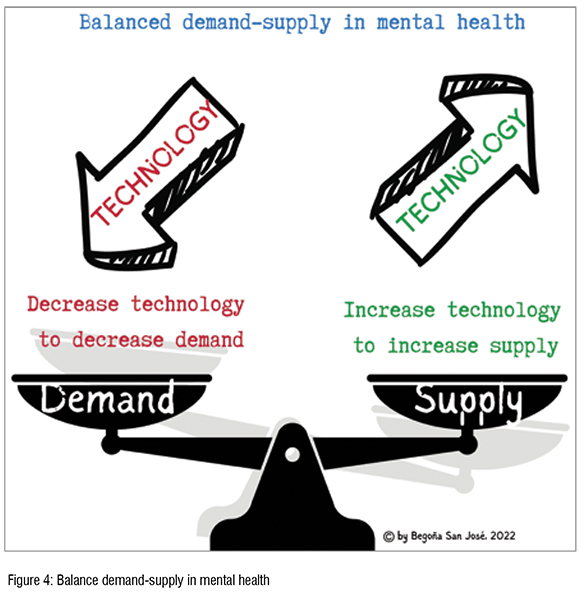

There is a demand-–supply imbalance in mental healthcare. The rapidly growing demand for mental healthcare services has met the undersupply and overstretched provision of healthcare services. Balance can be achieved by increasing technology to increase supply and decreasing technology to decrease demand.

The demand for mental health support is rapidly growing. The COVID-19 pandemic, looming financial uncertainty, the energy crisis, and armed conflicts, among others, have triggered significant worsening of the mental health of populations across the globe. This is reflected in sleeping difficulties, increases in alcohol consumption or substance use, symptoms of trauma, and suicidal thoughts. The prevalence of anxiety and depression has increased, and with it, the consumption of antidepressants and anxiolytics.

Simultaneously, and partly as a result of the measures to contain and limit the spread of COVID-19, mental health protective factors such as social connections with colleagues and friends and family, physical exercise, natural light exposure, daily routines, access to health services fell dramatically. Plus, mentally unhealthy lifestyles characterised by sedentarism, poor diets, high social media consumption, substance use and abuse, poor quality interpersonal relationships, isolation, sleep deprivation, lack of work-life balance exacerbated by teleworking and blurred boundaries between work and home, overweighted mentally healthier ones.

This dangerous cocktail affects larger and larger segments of the population but takes an especially high toll on the most vulnerable. Women, more likely than men to report mental health disorders, are experiencing burnout, especially those juggling increasingly demanding jobs, homeoffice and childbearing responsibilities. People suffering from chronic illness, and older adults, already at higher risk of having a concurrent mental health issue, experience an exacerbation of their vulnerability, both to a mental and a physical worsening of their condition. Children and young adults are experiencing mental distress due to disruption in routines, loss of social contact. Stress in the households is leading many to turning to social media and substance use as coping mechanisms. For those with disruptive family structures or exposed to abuse, the situation is even worse, and sadly, too many young adults are experiencing suicidal ideation. Healthcare providers and educators, often buffering thanks to their training and the social nature of their professions, are increasingly threatened by burnout. Last but certainly not the least, the situation for those already experiencing mental health disorders, is especially delicate since the increasing demand for mental health support of other segments, affect negatively their own ability to access services.

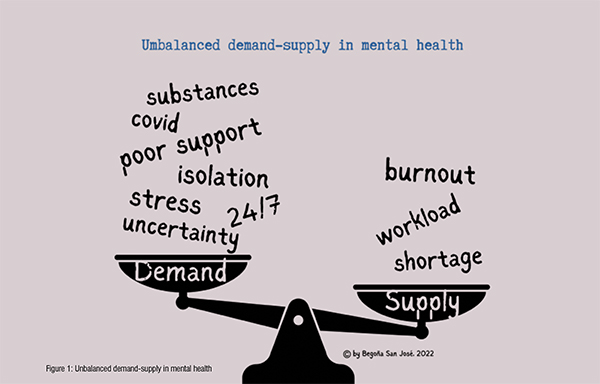

As illustrated above, there is an increased demand for mental health services. What is the situation like at the supply level? There is an undersupply of mental health support. The situation is not promising. There is a quantitative and qualitative shortage of mental health professionals, especially psychiatrists, who are working beyond capacity, who feel unable to meet the growing demand for support and who feel burned out. Waiting lists are growing and this increased workload is resulting in a reduction of time available per patient and are likely to impact outcomes negatively. To add on to the situation, the fragmentation in mental healthcare makes it difficult and inefficient to get supported while transitioning to the different levels of care. Figure 1.

In the current context, there is, therefore, an imbalance between a high demand for mental health services and a shortage in the supply of these needed services.

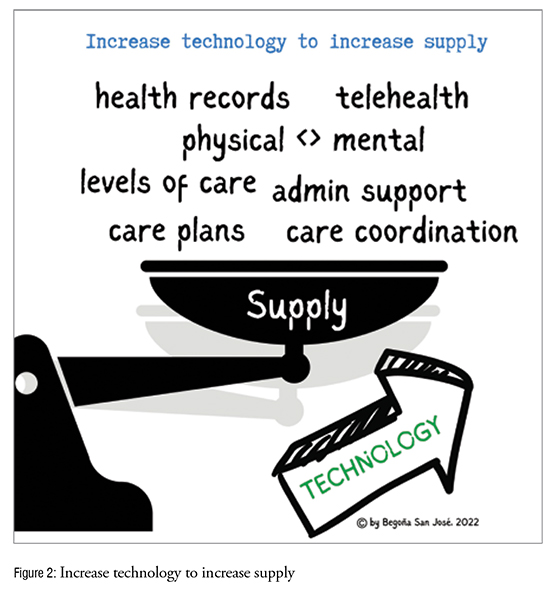

Technology can boost the supply of mental health support by improving access, quality, and efficiency.

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, telehealth has rapidly evolved from a nice-to-have to a necessity. Psychiatry has become the medical specialty with the highest rate of tele-consultations at primary-care level, granting access to those for which stigma had long undermined access to mental health support in a variety of ways. Technology facilitates access and updates on patients’ records, allowing care teams providing care for the same patients at a given moment or through time, to react more quickly to changes in a patient’s status.

Technology enables assessing the patient's needs and goals, developing a care plan, monitoring and follow-up care, supporting patients' selfmanagement goals, communication and coordination across multiple providers, facilitating transitions of care through levels of care and across providers, aligning and accessing resources to best meet patient’s needs, all of which result in improvements in quality of care.Figure 2.

Technology enables bridging physical healthcare with mental healthcare, breaking a historical barrier between the two and providing opportunities to better integration of behavioural and physical healthcare, especially relevant for the most vulnerable populations affected by both.

Technology enables behavioural health providers, psychologists, health coaches, health educators and others, to take on their respective roles and actively contribute to mitigating the effects of the shortage of mental health specialists and releasing them from cases that are more appropriately managed at lower levels of care.

Technology improves the efficiency of mental health practices by allowing collection and measurement of outcomes and progress, by facilitating access to resources and treatment options (including the prescription of lifestyle interventions or accessing selfmanagement tool and app libraries) and by facilitating unavoidable and time-consuming administrative tasks such as appointment booking and rescheduling, or billing, freeing up time for core activities directly impacting patient’s care. Technology leads to decreased healthcare costs, reduction in fragmented care, and improvement in the patient experience of care.

Technology works best in an integrated, connected system, supporting patients when they need care because they’re sick or helping them stay healthy. Self-management tools, designed based on the principle that people know what works best for them, should be easily accessible to patients and caregivers throughout the mental health continuum. These tools support patients in recognising what triggers a relapse and spotting its early warning signs, identify what, if anything, can prevent these relapses, tap into other sources of support, make an action plan. Technologically enables patients’ access to self-management tools timely, contributing to giving them the confidence they need to take active steps in managing their own problems at every stage.

When looking at the balance between demand and supply, one cannot look only at one side of the scale.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as a state of well-being in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community. Mental health is not defined by the absence of a mental illness or of life’s challenges. On the contrary, it is often adversity that shapes our mental health and well-being each time we face and we deal with difficulties. In simple words, mental well-being is the ability to respond to life’s ups and downs. It includes self-acceptance, sense of self as part of something greater, sense of self as independent -rather than dependent on others for identity or happiness-, knowing and using our unique character strengths, having an accurate perception of reality, knowing that our thoughts aren’t always true, having a desire for continued growth, thriving in the face of adversity (emotional resilience), having and pursuing interests, knowing and remaining true to our values, building and maintaining emotionally healthy relationships, being hopeful and having a mindset that supports the believe that things can improve, understanding that happiness comes from within rather than being dependent on external conditions and taking an active role in life, rather than waiting for things to happen.

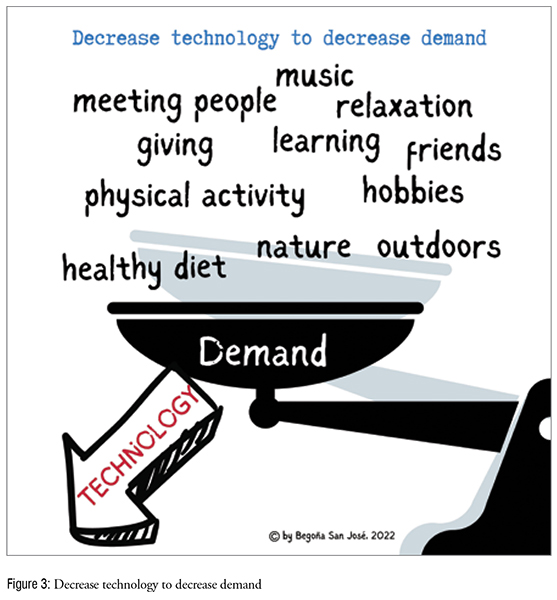

But we live in a digital-first world where from the start to the end of the day we are looking at a screen. With our mobile phones and computers we access the Internet e-mails, social media, at any time, anywhere, 24x7. This overexposure to technology, is not only affecting our sleeping habits, our ability to focus, as we are constantly distracted by incoming messages and notifications and exposed to a constant flow of information, but it affects also our ability to build social skills, and furthermore, an increasing number of people is addicted to technology.

How does our current lifestyle affect the demand in mental health? How can this overexposure to technology contribute to our mental health? How can social media consumption contribute to building and maintaining emotionally healthy relationships? How does our limited focus capability affect our desire for continued growth? To taking an active role in life? How does our work-life and our lack of spare time affect the use of our unique character strengths? Figure 3.

Just as lifestyle interventions such as diet, physical activity, or smoking cessation contribute to the reduction of risk factors associated with physical ill health, similarly, lifestyle interventions contribute to reducing the demand of mental healthcare services, reversing the trend. Which are these lifestyle interventions in mental health?

Connecting with other people face-to-face provides a sense of belonging and opportunities to share positive experiences. Despite the fact that technology facilitates connecting with people, it is easy to get into the habit of only ever texting, messaging or emailing people, leaving us with a feeling of isolation. Therefore, it is important to not rely solely on technology or social media to build relationships but to engage into in person contacts.

Contributing to a community and ‘giving’ creates a sense of self-worth, give a feeling of purpose, and provokes positive feelings. Learning new skills boosts self-confidence and self-esteem, help build a sense of purpose and often present opportunities to connect with others. Learning new skills, which can be achieved through learning to cook something new, engaging into crafts, trying new hobbies or playing an instrument, or reading on new topics, whatever resonates to the person most, helps getting new perspectives, gain new experiences, and trains the brain to handle a wide range of challenges, thus contributing to mental health and wellbeing.

Being physically active besides its well-known effects on physical health, it also improves mood, self-esteem, goal setting and achievement. Some forms of physical activity, like dancing, have a multiplier effect by being a physical activity, an opportunity for positive social interaction, learning a new skill or practicing a hobby. Hiking is also a physical activity, often social and in contact with nature. There are infinite possibilities and many of them act upon several dimensions. Practicing relaxation, meditation, yoga, praying, caring for pets or other animals, outdoor activities which increase exposure to light, spending time in nature, consuming or participating into artistic or creative activities, consuming or participating in music events, and practicing own hobbies are also activities that facilitate social cohesion and technological disconnection.

Putting all together, the balance between demand and supply in mental health can be achieved by increasing technology to increase supply and decreasing technology to decrease demand. Figure 4.

References: